Greener route

Abstract

A book’s journey from warehouse to retailer has a significant environmental impact. According to the BookPeople Sustainability Paper (2023), distribution alone accounts for over 63% of total emissions in Penguin Random House ANZ’s publishing operations. This article discusses the environmental impact of book distribution, particularly the last-mile journey. We draw upon interviews with distribution leaders from Hachette and Penguin Random House; to discover how major publishers are responding to challenges of sustainability in outbound logistics. In doing so, we found that there is a lack of actionable solutions being implemented—confirming that current industry priorities of speed and convenience dwarf environmental considerations.

Jord Littlejohn, Alice Wanless

What are the key aspects that the publishing industry should be considering to get distribution on a greener path, especially in the last-mile journey from warehouse to retailer?

Keywords: distribution, electric vehicles (EVs), last mile distribution, sustainable practices, technological barriers

Introduction

To survive in a climate-conscious future, the Australian publishing industry must reshape how books are delivered to readers. Though publishing is often associated with literary and artistic expression, the Australian publishing industry is deeply embedded in material and logistical processes, many of which create a significant environmental impact.

In particular, outbound transport—the movement of books from publishers/distributors to retailers—is a major contributor to the industry’s environmental impact, but as conversations around sustainability in publishing have prioritised a focus on paper and digital formats, there is still a need for more sustained focus in the impacts of outbound transport.

In our article, we focus on the role of transport within the environmental sustainability efforts of the Australian publishing industry, specifically looking at the ‘last mile’, a logistics term referring to the final leg of a product’s journey from warehouse to retailers. This is a crucial yet often overlooked stage—frequently the producer of high greenhouse gas emissions and inefficiencies in metropolitan freight transportation systems. Australia’s vast size, relatively small population and wide separation of major cities create a unique logistical challenge to sustainable last-mile freight.

As publishing continues to evolve, it is crucial not only to tell stories responsibly but also to consider the ethical implications of how those stories physically arrive in readers’ hands. Examining transport not as a neutral process but as an active site of environmental consequence highlights the urgent need for structural innovation.

Key concepts

The circular economy

The circular economy—the concept of restructuring industrial systems so that the waste from one process becomes the input for another—has become increasingly significant in discussions around sustainable logistics and supply chain improvements. Aiming to achieve both ecological and economic benefits, this model is based on five key dimensions: Reduction, Reuse, Recycling, Recovery and Remanufacturing. These processes encourage organisations to minimise waste generation while extending the life cycle of materials and products.

Some researchers argue that circularity is the ‘optimal solution’ to achieving sustainable growth amid escalating environmental crises. The principle of recovery, particularly through the collection and redistribution of end-of-life products, can be facilitated in the context of distribution by strategically located distribution centres. This could involve partnerships with booksellers and third-party logistics providers to manage unsold or damaged stock through warehouse returns and resale, therefore reducing waste and emissions associated with landfill disposal.

While these strategies are discussed in theory, there is limited evidence of their widespread adoption in publishing, suggesting a missed opportunity to apply green supply chain thinking to outbound logistics.

Infographic 1: a circular economy.

Emissions and distribution

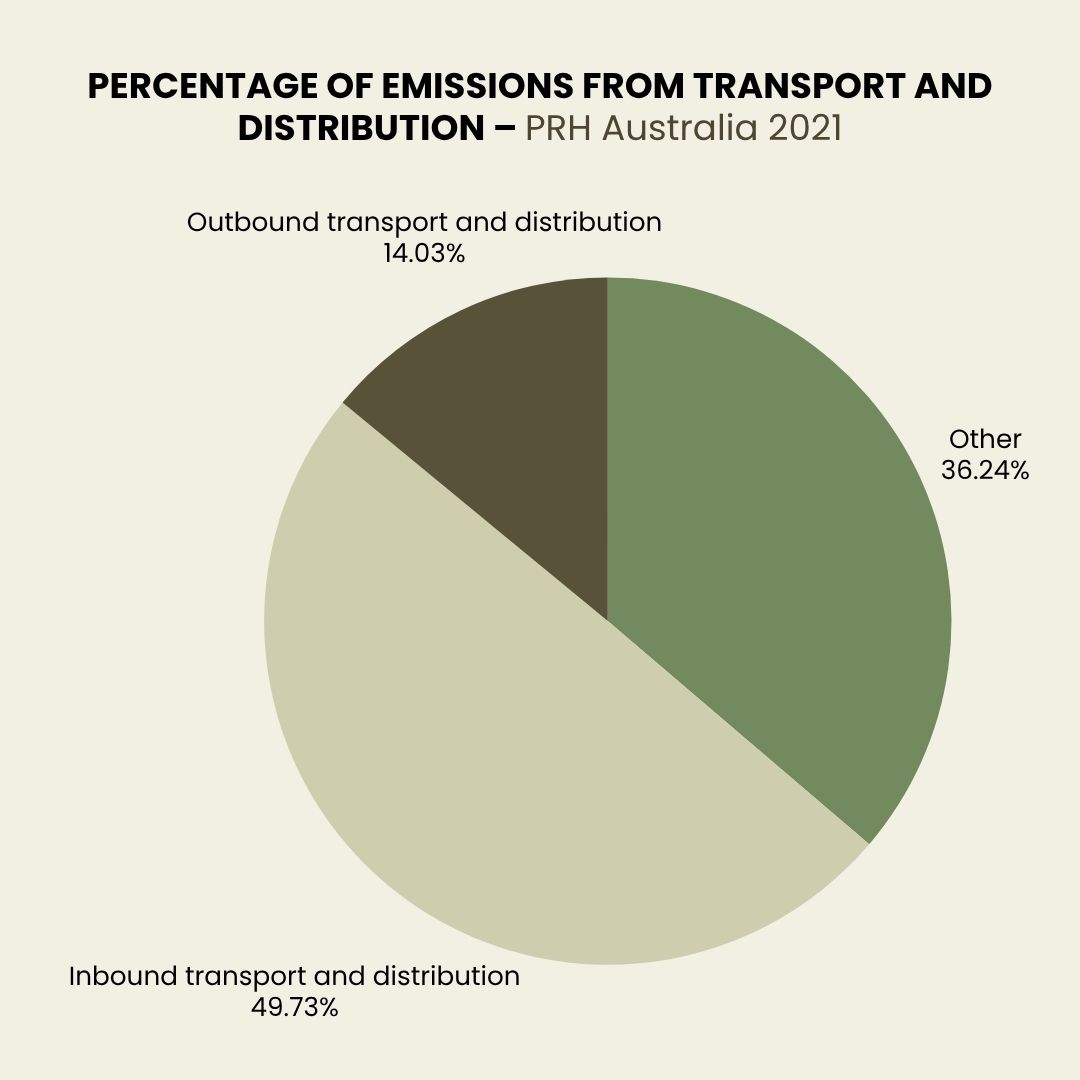

Transportation and distribution operations are among the largest contributors to emissions in the publishing supply chain. Inbound freight alone accounts for 63% of the total carbon emissions of Penguin Random House Australia and New Zealand (PRH), highlighting the environmental cost of moving and transporting materials before books are even reaching booksellers. Whilst data on outbound freight by PRH and other industry stakeholders is lacking, packaging and shipping also cause significant environmental damage, such as cardboard and plastic waste and fuel-related emissions.

In response to these issues, international standards such as ISO 14001 offer a framework for environmental management that emphasises life cycle analysis at the centre of supply chain decisions. The standard calls for measures to be taken to manage environmental risks inherent in the aspects of the distribution process that are particularly high in emissions, such as transportation and warehousing, and encourages organisations to set measurable targets or Environmental Performance Indicators (EPIs).

As a result, publishers such as Hachette UK have adopted a comprehensive life cycle approach and committed to reducing supply chain emissions by 25% by 2030, based on metrics set by Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi). Similarly, Penguin Random House Distribution (PRHD), formerly known as United Book Distributors (UBD), has completed a carbon footprint inventory to explore more sustainable logistics solutions. Although these efforts indicate recognition of the environmental impact of book distribution, our research has highlighted the need for more transparent reporting and standardised emissions metrics across the industry.

Case study: Alliance Distribution Services

Alliance Distribution Services (ADS), owned and operated by Hachette Australia in Tuggerah, Central NSW, plays a significant role in the supply chain logistics of Australian publishing. ADS provides distribution not only for Hachette, but also for multiple small and mid-sized publishers (including Magabala Books, NewSouth Books, and Phaidon). By operating as the central distributor of multiple companies, ADS reduces the number of deliveries needed, condensing shipments and grouping all the publishers under their wing into a singular mode of transport.

Riikka Dunn, the Director of Distribution at ADS, stated in our interview that freight carriers only operate in locations where there is a demand, and therefore the frequency of orders from bookshops dictates how many times a week their vehicles are on the road—up to four times a week to the one retailer in some instances. Dunn argued that the responsibility of the last-mile deliveries falls away from her and ADS, and on the shoulders of the freight carriers themselves, as ‘freight carriers could be delivering books as well as other items to Big W and it's there as a possibility to do that last-mile freight optimisation when you're then looking at bookshops in Australia they will only get books [sic].’

Dunn expressed interest in EVs, however, ‘given the current situation with the government not having much in the way of economic benefit’, she ‘doesn’t see it happening any time soon’. While ADS may be looking into EVs, Dunn said that other distribution companies have no obligation to begin converting to EVs. ADS need to ‘move books from [their] warehouse across the entire continent’ and, as such, explored alternatives such as rail freight for long-distance deliveries to Western Australia. However, the challenges of rail—limited capacity and scheduling inflexibility—prompted a return to road transport.

So, with the infrastructural limitations still at play, ADS has considered EVs for road freight, but this remains economically infeasible due to cost and other infrastructural constraints such as the lack of charging stations—especially in more rural areas, as is needed for freight being moved from NSW to WA. The efforts are, as Dunn expressed, ‘not going to happen any time soon,’ but there have been major strides in the right direction.

Case study: Penguin Random House

PRH Australia, as a major industry stakeholder, publicly announces its environmental sustainability efforts, particularly within freight and the last-mile journey, through its corporate reports detailing sustainability practices and progress. While PRH Australia recognises the detrimental environmental impact of freight, its most recently published reports offer minimal detail on emission levels from outbound delivery.

In 2022, PRH Australia conducted its first comprehensive carbon emissions analysis through an independent third party and generated a report examining its 2021 carbon footprint. PRH Australia revealed in the following 2022 report that indirect freight accounted for 63.76% of its total emissions. Inbound transport and distribution accounted for a majority of this (49.73% of total emissions), with a significant portion being international freight delivered by sea and air. PRHD is responsible for their distribution logistics. In a post on PRH Australia’s website reporting on their emissions, the company acknowledges that reducing their indirect transport emissions is ‘no quick fix’ and requires ‘a long-term shift in production.’ Nevertheless, specific breakdowns or comments on outbound transport and distribution, which make up 14.03% of total emissions, are largely omitted.

Infographic 2: Transport emissions, PRH Australia 2021.

In a 2022 Q&A published on PRH Australia’s website, Operations Director Matt O’Brien outlined PRHD’s sustainability priorities, emphasising the company commitment to making distribution more sustainable through improvements in warehouse and packaging efficiency. Some initiatives included the redesign of cartons to fit more books per box, which reduced overall shipping volume, resulting in 5,200 fewer pallets and 225 fewer trucks on the road annually. PRHD also adopted thinner, more efficient pallet wrap that halved plastic usage and cut plastic waste by eight tonnes each year.

O’Brien notes the inspiration behind these changes came from the significant contribution of inbound and outbound freight to the company’s total emissions, as recorded in the 2021 report. He further highlighted the strategic role that the distribution centre has in reducing emissions by optimising packaging and logistics and stressed the importance of influencing delivery partners to reduce the truck numbers and adopt sustainable practices.

According to O’Brien, the single most important change made so far is the step-by-step approach that PRH Australia and PRHD has adopted towards sustainability, pointing to collaboration between freight and production partners to ensure emissions reductions across the entire supply chain. To conclude, when asked what change he would like to happen in the next five years, O’Brien proposed a more localised supply chain that would reduce reliance on international freight.

While these initiatives demonstrate a clear intent to address freight emissions, measurable progress has been modest. There are signs of incremental progress, with the release of the 2023 Sustainability Report in 2024, showing transport and distribution account for 33.49% and 29.82% of PRH Australia’s total emissions, respectively. This decrease of less than half a percent from previous figures highlights that while strategies are in motion, the tangible impact on overall emissions remains limited. In March of this year, Matt O’Brien relayed the same sentiment, stating that ‘inbound and outbound freight remains the biggest impact on [PRH Australia’s] footprint.’

Moving forward in 2025, O’Brien emphasises that PRH Australia’s strategy is to ‘reduce [their] reliance on freight by localising the supply chain as much as possible’ and investing in packaging innovations aimed at reducing its transportation footprint. These changes have led to tangible results, including a 12% year-on-year reduction in emissions from outbound freight in 2024, highlighting the ongoing attention to the challenges posed by concerns surrounding sustainability.

Challenges and opportunities

Electric vehicles

Electric vehicles (EVs) are increasingly being considered as viable, low-emission alternatives in the distribution process. In 2023, the adoption of EVs in Australia more than doubled, supported by a 75% increase in charging infrastructure nationwide. The Australian Government’s National Electric Vehicle Strategy outlines a strong commitment to reducing emissions in transport sectors, including freight and last-mile delivery (LMD), by supporting increased EV use. Moreover, the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) highlights that the integration of electric fleets with renewable energy sources significantly enhances the environmental benefits of EV adoption, moving beyond vehicle emissions to a more sustainable energy model.

Publishers who deal with high transport emissions could explore shifting fleets or collaborating with EV-based courier services, especially for metropolitan deliveries and warehousing, thereby reducing environmental impact and aligning with Australian sustainability goals. Despite growing accessibility, EVs remain a largely unexplored avenue in publishing logistics, indicating that it is an area for potential innovation.

There is currently an Electric Car Discount, introduced by the Government in 2022, which exempts eligible EVs from the fringe benefits tax and removes the 5% import tariff on EVs, helping to make EVs more affordable by reducing upfront costs. It is interesting that the companies aren’t taking advantage of this, or perhaps the incentive is seen as too small. Regardless, it appears that the Australian Government is not doing enough for organisations like ADS to make the change. This, in turn, leads to the overarching issue: the economic benefit of continuing to use internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles outweighs the environmental benefit of converting to EVs.

ARENA’s Driving the Nation Fund has allowed for 112 battery electric vehicle (BEV) trucks to be on the road, making LMDs due to their $12.8 million in funding. These trucks are all within the company ANC, who deliver for many big companies such as Bunnings, JB Hi-Fi, IKEA, and The Good Guys. The addition of these trucks, as a conversion from their ICE trucks, will greatly reduce the company’s GHG emissions. ARENA CEO Darren Miller said the program is working to achieve an electric LMD system in Australia ‘by lowering the total costs to own and run electric trucks.’ While the current situation is still in favour of ICE trucks, the landscape is becoming more open to the possibility of EVs, especially for LMD for commerce.

The implementation of any kind of system that aids in reducing GHG emissions in inner-city areas is rare. Both Riikka Dunn and Matt O’Brien knew about EVs, and while Dunn said that ADS had specifically looked into their usage, O’Brien had said that PRH were attempting to ‘[localise] the supply chain as much as possible and [invest] in packaging innovations that lower [their] freight footprint.’ This again demonstrates the importance of cost-effectiveness; is the company going to be getting back what it spends on setting up these systems? Matt O’Brien further commented that ‘with advancements in technology and transport, we could have electric trucks transporting the stock around Australia’, demonstrating that these companies are waiting for the push, that the technology isn’t where they need it to be.

Urban centres

In addition to EVs, last-mile freight delivery in urban centres could mobilise other environmentally friendly transport options. Inner-city last-mile delivery is a major contributor to urban congestion and carbon emissions, largely due to failed deliveries, fragmented delivery routes and underutilised vehicles. These challenges point to a need for improved coordination between both parties, couriers and retailers, and in response to this, a number of innovative solutions have been proposed.

Urban Consolidation Centres (UCCs), which are smaller depots located just outside of cities where books can be stored via road freight, aim to streamline freight logistics by consolidating goods for multiple recipients at a time. The hubs would enable shorter, more efficient trips to urban areas for the last-mile delivery, ideally undertaken by low-emission vehicles, therefore reducing both traffic congestion and carbon output. The vehicles, ideally smaller EVs like bicycles, would need to be strong enough to hold the 16kg boxes that Dunn said ADS limit their boxes to. This pulls in a constraint on its own; the deliveries would have to be continuous if a single courier is only capable of delivering one box at a time. Dunn expressed interest in the idea but suggested that ADS hadn’t looked into it yet.

Another emerging model is containerised last-mile delivery. The system involves staging pre-packed containers at strategic hubs, which can then be distributed via e-bikes or EVs—offering a more sustainable and reliable alternative to traditional delivery methods in dense metropolitan areas. For the publishing industry, such strategies are particularly applicable to bulk deliveries to schools, libraries and bookstores in urban landscapes. Consequently, publishers that manage high volumes of shipments to urban areas could benefit significantly from these innovations, improving both their environmental footprint and logistical efficiency.

When prompted to speak on the movement of books through inner-city areas, Dunn said that ‘books can be quite heavy,’ and because of this limitation—especially regarding ‘scooters’ or ‘bicycles’—she said that ADS had ‘look[ed] at EV deliveries’ and had pushed their freight forwarding companies to see what EVs look like and what sort of … fleets’ they could invest in. Dunn mentioned that ADS ‘don’t own [their] trucks’ but that they were ‘trying to use [their] leverage in that sense’ to push for the trucks they don’t own to be converted to EVs for environmental sustainability.

Other initiatives

In our interview with Robbie Egan, CEO of BookPeople, he mentioned that PRH distribution have changed their boxes so they can ‘move to fit more or less books and therefore take up less space in trucks.’ This leads to the reduction of trucks on the road, as more boxes can fit in each. He said that while there are advantages to these new designs, the largest flaw is that they are more difficult to recycle or reuse, with booksellers having more trouble using them for returns or bulk sales.

Alongside the new box designs, Egan said that there has been a shift in void fill materials, moving away from starch peanuts—which are biodegradable, compostable, and even edible—towards air-filled plastic bags. These plastic bags are biodegradable, but Egan says that ‘they are more effort to recycle and therefore often end up in waste anyway—especially through bookstores.’

Many of these new waves of recyclable packaging are unfortunately single-use, which leads to a linearity in the economy, rather than a forward-moving circular economy. The single-use plastic bags and peanuts need to be constantly manufactured for their use and are using GHG-emitting machinery to do so.

Findings

Many of the aspects that we have come across in this report while focusing on the benefits of a greener last-mile delivery have been that of incidental environmental sustainability through attempts at economic sustainability. This can be seen in the drastic reduction in air freight, which was originally a result of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions but has now become a staple in the industry due to the economic benefits of alternative shipping methods. The lack of air freight helps with environmental concerns, but that was not the sought-after goal of the companies that implemented the systems.

Incidental environmental sustainability as a result of economically sustainable initiatives is something that could be further researched and complemented by legislation. Required subsidisation of EVs, for instance, would make buying and running them both logistically feasible and affordable.

In the case of ADS, their core goal is clearly to be the distributors of more than Hachette’s books. Although Dunn noted that the current initiatives in place at ADS have very rarely been driven by environmental concerns but rather by the desire to make systems more cost-efficient, the conclusion remains the same: consolidated shipments cut down on vehicle usage and therefore GHG emissions. Through the collaborative model, ADS reduces the number of trucks on the road, contributing to lower greenhouse gas emissions—an increasingly relevant issue across the industry’s supply chain.

ADS demonstrates the challenges faced by a large publishing distribution centre when environmentally conscious decisions are wanted (or needed), but not cost-efficient. The likelihood of these larger companies moving to more sustainable practices is minimal, until or unless there are incentives to do so. The government is slowly finding ways to get EVs into the system, but with the processes involved in making the batteries, recycling them, and generating infrastructure, it becomes less feasible. By centralising distribution in their Central NSW location, the company is playing a role in decreasing the number of trucks on the road—hence, carbon emissions—and that is a positive. However, it seems that most companies are hindered in their progress: even when they know how to improve, they hesitate to implement change if it means a financial loss.

Although policy change could dramatically accelerate progress, there is currently little government support to propel such shifts within the freight and logistics domain. In our interview with Robbie Egan, CEO of BookPeople, he emphasised that there is little in the way of government assistance through ‘tax breaks or subsidies.’ With government assistance, such as ‘tax breaks on buying them,’ EVs could become more widely accessible and therefore more widely used. While EV batteries have been looked at as a potential problem, according to the Australian Government’s National Electric Vehicle Strategy they can be and are being reused and recycled.

In 2021, ‘Australia recycled 99% of lead acid batteries, compared to just 10% of lithium-ion batteries’, but some research suggests that Australia could produce a battery recycling industry ‘worth $603 million to $3.1 billion in just over a decade.’ This shows an opportunity to make an economically advantageous change that may also reduce environmental harm.

This research suggests that financial benefits will be the key driver of change, as innovations that improve environmental outcomes are adopted based on whether they are also profitable (or at least not costly). For instance, a company that switches to EVs now, with the current limitations on government aid, will likely not get back what they paid for the EVs until a much later date.

So, what incentives are there for a company to spend more than they will get back? One consideration is consumer pushback to the lack of systems and initiatives within the publishing industry that are helping to reduce GHG emissions. As in our interview with Professors Paul Childerhouse and Priyabrata Chowdhury, there is a reputational risk if a company goes against a large consumer base that opposes the company’s lack of effort to reduce their GHG emissions. Childerhouse specifically stated that ‘reputational risk is probably the best hope we have’ in a greener publishing industry. So, then is it up to us, rather than the industry, to push for change?