THE RIVER BESIDE US

Zachary Edwards, Thea Oakes, Taras Rego and Linh Tuong Vy Nguyen

She watched as little black cormorants made their way through the piles of trash that collected in the catchments. They were using rubbish barges to roost. She knew that the Yarra had not always been such an unappealing home for its inhabitants. Flocks, almost innumerable, of teal ducks, swans and minor fowls had rested there 180 years ago. It was near impossible to imagine what an amazing place the Yarra had once been. As well as the obvious pollution issue, introduced pests reduced the number of native birds in her city.

She knew that her friends didn’t care about this. To them the Yarra had always been just another addition to a city they knew too well. They had to cross bridges to get from one side to the other and the boat trips it hosted were only for tourists. They didn’t notice the birds gliding along the water’s surface, and probably wouldn’t have noticed if they disappeared altogether.

Her mum had told her that, years ago, dolphins sometimes made their way into the Yarra from the bay, chasing fish with the sun shimmering on their backs. She knew this river was important, if only for its unique fauna. Looking out at the river from Princes Bridge, she had more questions than answers.

He strolled down Flinders Walk, phone clutched in hand, the battery about to go flat from snapping photos all morning. He had only known Melbourne for a few weeks. The excitement of exploring a new city and impressing friends back in Vietnam had him buzzing. The Yarra River seemed like the most promising location for his next Instagram post.

From Princes Bridge, he allowed himself to get lost in the scenery of the Yarra, from the water that peacefully coursed under the bridge to the vibrant grass and eucalypts that ran along the river banks. Looking out, something caught his eye: a flock of small black birds that swooped down on the river’s surface looking for catchments.

“Dất lành chim đậu”

He immediately remembered an old saying from his culture: đất lành chim đậu, meaning ‘where there is good land, birds will build their nests’. Hundreds of years ago Vietnamese people realised that birds would only appear in areas that were blessed with utmost prosperity, where all natural elements mingled in harmony, ensuring a fulfilling life for those residing there. This became one of the most crucial criteria for Vietnamese kings to decide where to build their castles, and for monks to choose a sacred ground to build pagodas and shrines.

The joyous chirping of a magpie brought him back to the present.

He’d heard that these birds were believed to carry the spirits of ancestors watching over their land and give blessings to those who lived there.

He started to wonder at the history of the land. As he tried to spot more birds, telltale signs of the land’s past, he became curious about the river that he took so many pictures of but knew so little about.

She exhaled slowly; a long, deep pause to align herself with the calmness of the river. A soft breeze made the trees whisper. Thousands of years of secrets passed from leaf to leaf. Surely she wasn’t the only one here who saw the Yarra’s beauty?

She saw, in the corner of her eye, a young man taking selfies, his back pressed against the ledge of the bridge, where he struggled to fit his wide smile into the narrow frame. She smiled and offered to help, and turned his attempted selfie into a worthy portrait.

The dark cormorants gathered in the near distance, some as still as statues, as they demanded for more of his photos. Together they laughed and looked on, as the birds posed and fought their way to the peaks of waste, as if they were aware of their human audience.

It wasn’t long before the couple’s shared curiosity of the river came to the surface. Puzzled about its history and significance, neither were able to answer the other’s questions. She remembered a school excursion she had enjoyed a few years earlier at an Indigenous education centre close by. His growing desire to learn about the river was inspiring and she felt motivated to know more too. At first, he only cared about his followers back in Vietnam, but with each step they took toward Federation Square, she knew he was becoming more interested in the Yarra itself. They wandered in the sunshine towards the arts and culture centre of Melbourne, an icon for both locals and international visitors. The large, black sign read Koorie Heritage Trust. They followed it, both fielding a passion to learn more about what the river used to be.

The guide took them inside, up the turning staircase with colourful Indigenous Australian paintings hanging on the walls, and into a room filled with ancient artefacts. They stopped at a long table full of drawings, maps and models of ancient tools. Their eyes widened and they gasped at the breathtaking oil paintings of what the Yarra River once was. The water was crystal-clear—a fragile, duck-egg blue—like a delicate strip of silk, seeping smoothly past villages of the Wurundjeri tribe. A curtain of white water cascaded over the grey rocks, forming a waterfall that tumbled into the river. Lush green of gullies, fern trees, sugar gums and tea-trees hugged the river banks.

The guide explained that the Yarra River was once known as the ‘Birrarung’, which translated to ‘river of mist’. The ‘Yarra Yarra’ was the name of the waterfall, which settlers misunderstood to be the name of the river itself.

‘When you go down here in summer you can smell the lemon in the air, it’s beautiful, but the wattles and banksias would have created a blue hue over the river that would be there most days and most afternoons and the trees would cast shadows, so it’s called the river of mists and shadows, that’s what it really means.’

Melbourne from the falls

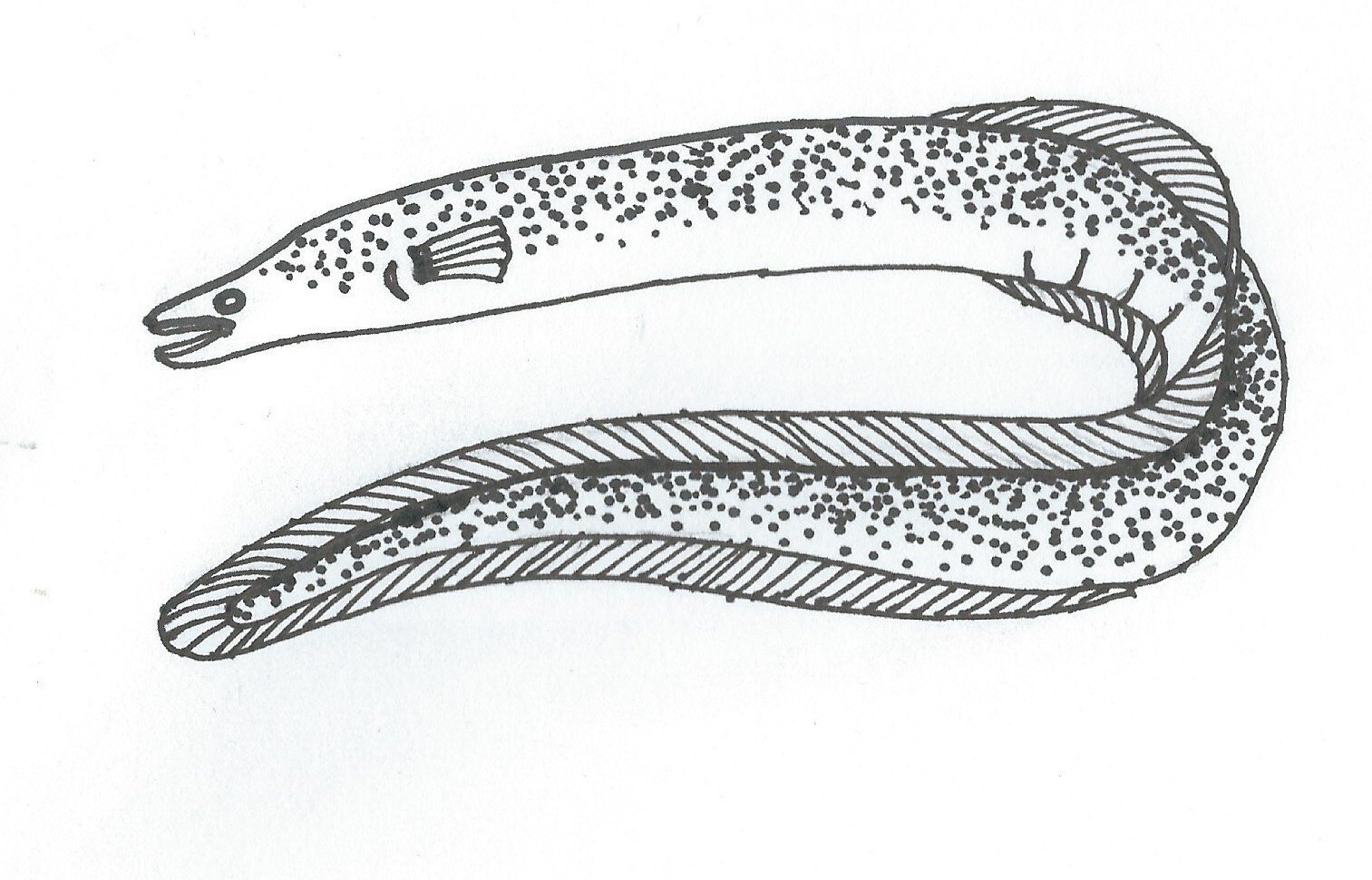

The guide said that the Birrarung was a prolific food source for the short-finned eels and sand mullets that called its waters home. Indigenous Australians used branches, grass and vines to make fish traps, easily catching the abundance of slithering creatures for hearty meals.

‘This [the woven funnel of the fish trap] would be tied up and floated down the Yarra so the fish and eels would run into the neck. These guys [the fish and eels] would be so upset because once they got through the trap door on the other end, they would not be able to go past the same trap door again. The small layout of the trap prevented them to swim backwards and their bodies were too long to bother.’

He traced his hand along the model of the fish trap that the guide handed him.

Eel trap

It took him back to the fishing village that his grandparents came from. Backto that dusty cottage where Grandma would weave fish baskets with bamboo and palm wood. The wood would be woven into funnels, with a long neck and a trap door to keep fish inside without letting them swim backwards, just like the ones made by Indigenous Australians. He thought about his beloved hometown, and the foreign river in this foreign land suddenly became strangely familiar.

He realised exactly what made the Birrarung so special. Birrarung was Mother Nature to the people living alongside it; she blessed her children with an abundance of food and resources to ensure they would thrive.

Eucalyptus tree

The Koorie Heritage Trust walking tour took them through locations they had been before; past ArtPlay where she had finger painted and attended writing workshops as a child; past grassy hills where he had sat with his friends and pigged out during the recent noodle market. The area was named Birrarung Marr—a name they recognised from their guide’s story of mistranslation. They both had memories on this land yet had no idea of its history or even what magic it held in the current day.

Their guide led them to a eucalyptus tree next to the Federation Square car park. He shook the branches and explained that in summer white granules would rain down, drifting like tiny snowflakes to the ground. Examining the tree carefully, he showed them white lumps attached to the leaves. He told them that it was a natural sugar, often called aperaltye, which Indigenous Australians used as a sweetener. Sheets or bowls would be placed underneath to catch the natural sugar as it fell from the branches, sometimes being rolled into balls and given to children as treats.

The guide showed them a portion of ochre from a nearby rock and encouraged them to try drawing on the concrete. It reminded her of drawing hopscotch squares on the pavement in primary school. It reminded him of the school chalkboards in Vietnam. The tour finished where their questions had begun. It was a beautiful winter day, the wind whipped up peaks in the water which glimmered in the sunlight. Looking over the river their guide told them that ‘sharks, stingrays and eels would come up and dolphins have been seen in the river’. At the thought of dolphins again, she secretly hoped one would appear at any moment.

As he strolls along Flinders Walk to get back home, he looks at the birds rushing home before it gets dark; this time he knows their names.

As an international student living in a strange land with unfamiliar culture and people, he often felt left out. But now, he is no longer alone—instead, he can feel his family walking with him. He can hear his grandmother telling him that the black ducks and wood ducks on the river banks represent united bliss and tight-knit family community. He can hear his grandfather telling him that the magpies in the trees bring good fortune and blessings. He can hear his parents explain that the white-faced heron and nankeen night heron, like the ones far on the other side of the river, symbolise tranquillity, wisdom and longevity.

To him, he knows he will always remember this walk with the Koorie Heritage Trust. The Birrarung brought him closer to home, even though he is thousands of kilometres away.

For her learning that the Yarra River was once named Birrarung opened up a whole new perspective. A river full of life and resources, with so many natural uses. No longer just a waterway that she and her friends knew nothing about, she is now able to connect what it was before to how she experiences it now. She can see beyond its murky waters and discover a newfound respect and love for the river. She is astonished that so many settlements had formed on its banks. The Birrarung connects these living cultures.

The Birrarung is vital to the Wurundjeri people, who once depended on the resources abundant on the river’s banks and still deeply value the river to this day. Settlers also found promise in what the river had to offer. To this day the Birrarung is imperative to our community; its history is invaluable, and its future is essential.