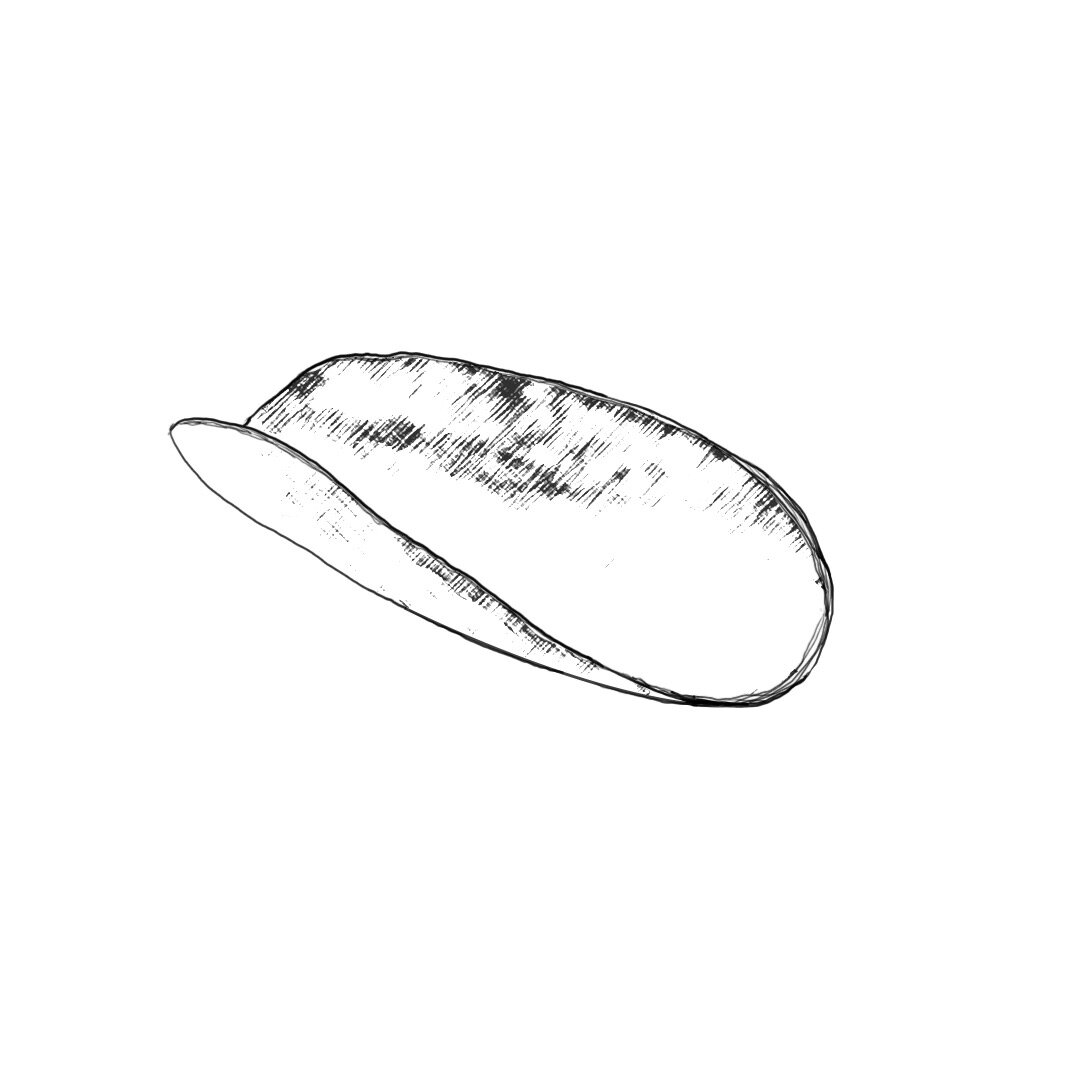

Standing in the shadow of the MCG, I realised that it wasn’t what I was expecting. With a fence for protection, I had to peer rather close to see the indented, shadowy marking in the centre of the gum—the reason for its name the scar tree.

Before the walk I anticipated towering, majestic gums with large, gaping scars, home to a variety of chirping magpies and wide-eyed possums. Instead I found myself in front of a short bushy gum covered in green branches. It stood alone, surrounded by freshly cut grass and playing children. The tree was as wide as it was tall and careful effort had to be made to avoid getting hit by a rogue branch released by a mischievous classmate. I was genuinely surprised by its mundanity. The scar was mostly hidden under dense branches, its jagged outline moulded and reshaped repeatedly over time.

Surveying the size of the structure, I was shocked by how many times I've been in that very spot and not noticed it. It’s a tree I walked past nearly every week on the way to work, in the quiet hours of the morning, and on weekends in the afternoon to cheer on my favourite footy team. I’d never glanced at the plaque at its base or admired the trunk’s intricate patterns. I’d never really known it was there.

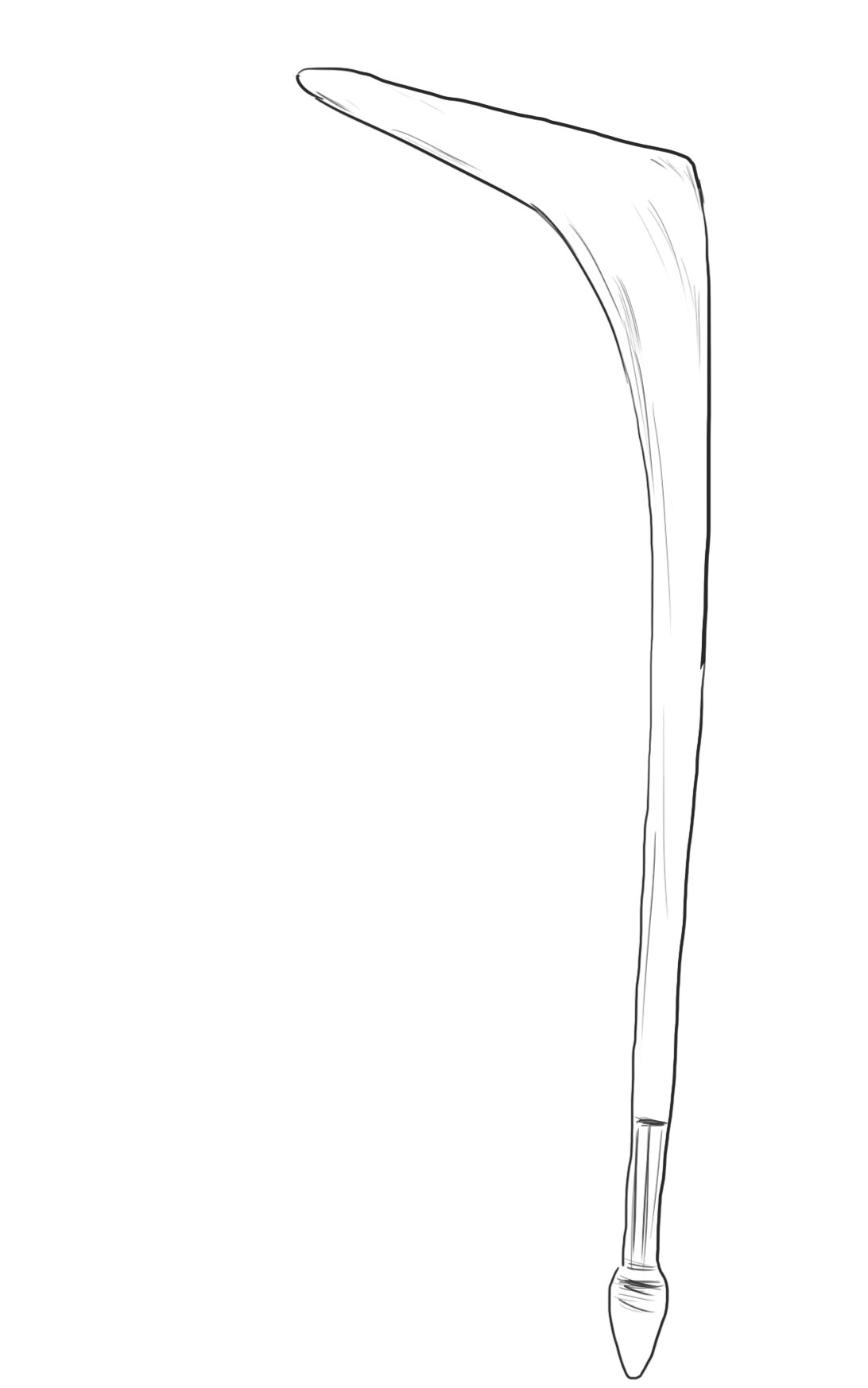

A couple hundred metres up the hill was another, less-alive looking scar tree. Although its days of greenery were in the past, its sheer presence remained. Barer in branch density and foliage than its sibling, this tree looked striking next to the looming concrete of the MCG.

Our guide explained how this scar was made by an intricate and delicate process of bark removal carried out between 200 to 800 years ago by the Wurundjeri people.

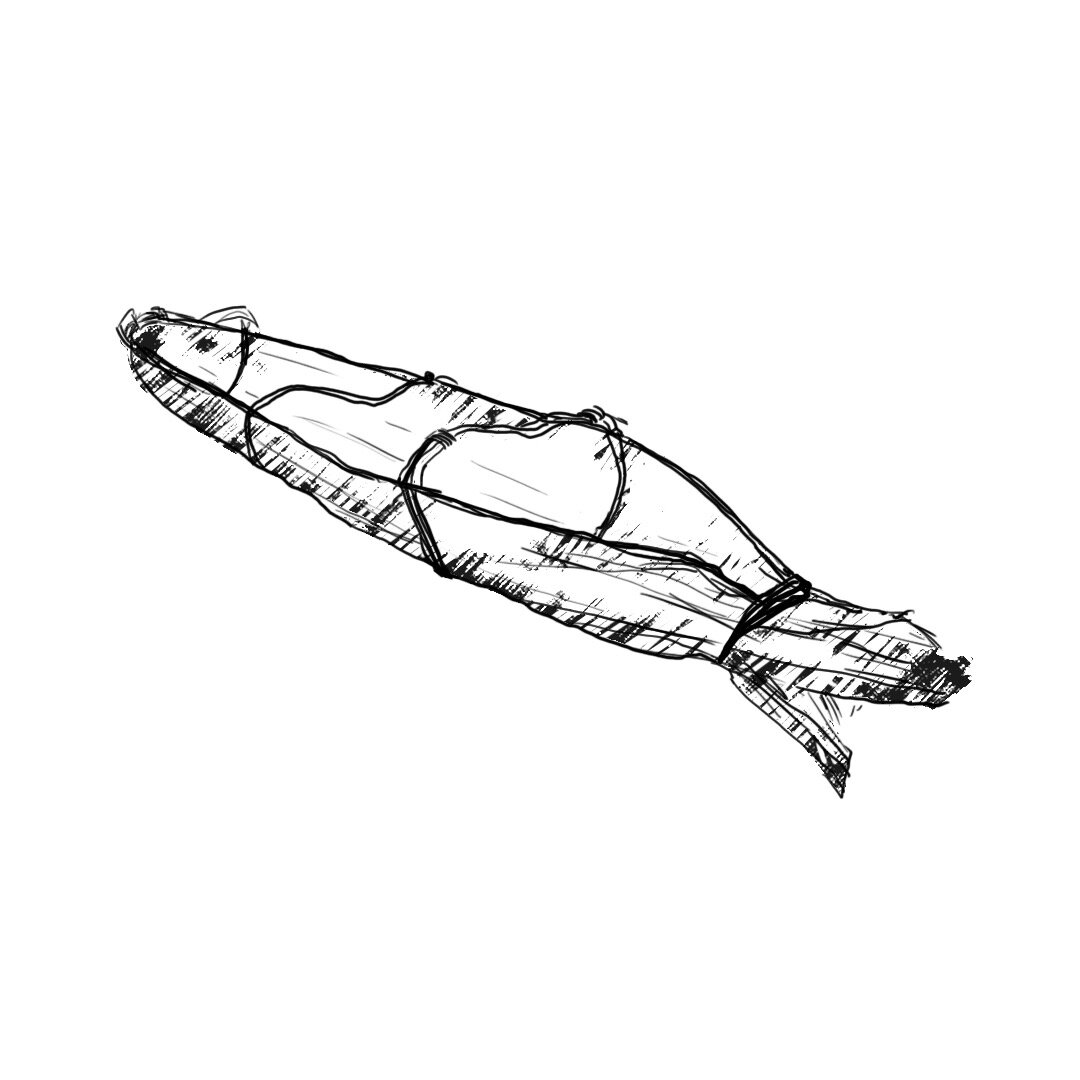

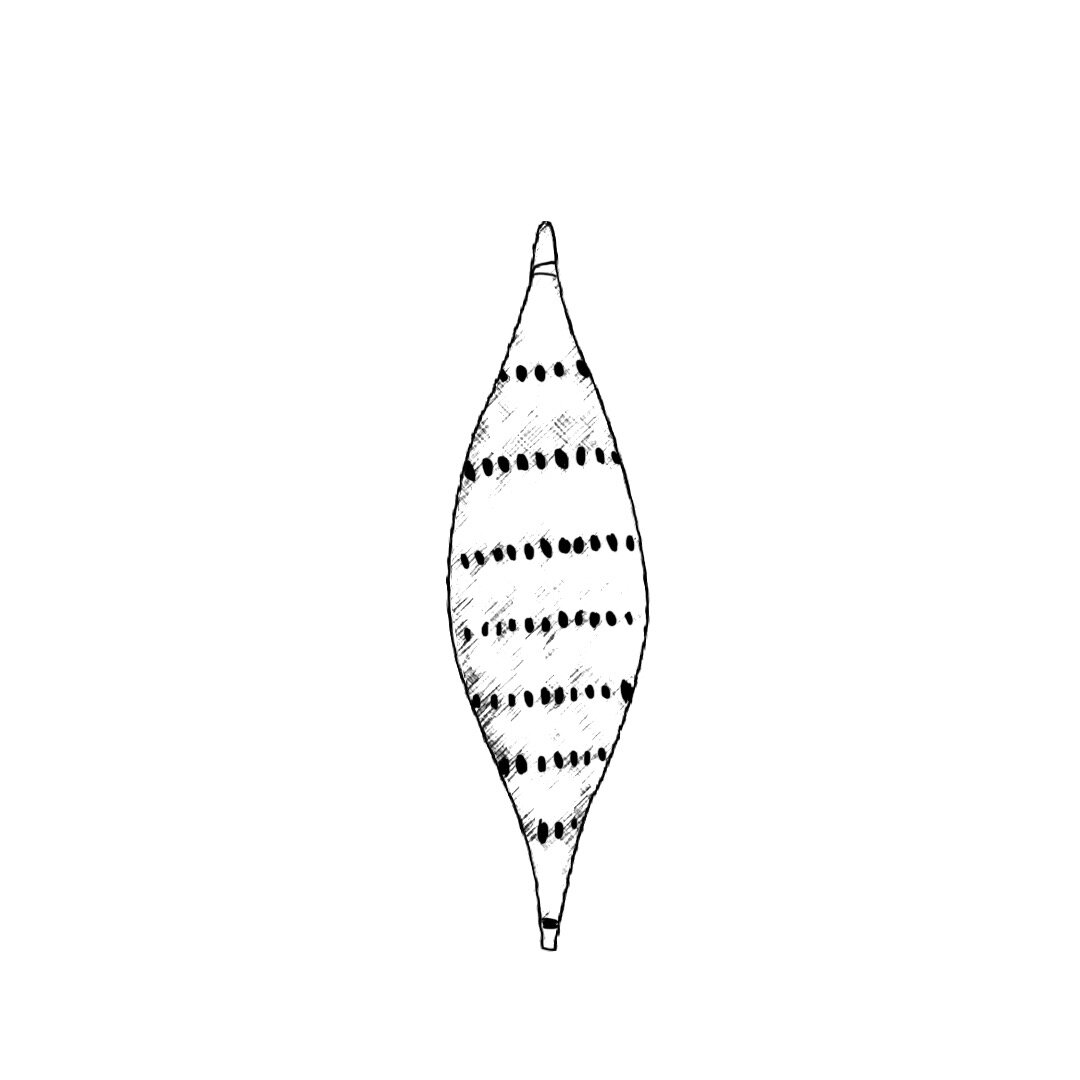

These trees, resolute and quiet in their physical presence, share the history of Aboriginal people’s land and culture. The bark, once removed for use in everyday life, leaves a powerful visual. Without cutting down the tree, local Aboriginal people would harvest the bark to create items such a coolamons: simple water containers3.

The location of these trees near the river suggests their bark was used to create canoes, giving the traditional owners of the land easy transport along the closely situated river. This opened up travel routes and allowed tribes access to a larger array of resources and liveable land4.

I listened patiently and learnt that while this is the most documented type of scarring, other forms of scarring include deliberate marking of trees as border landmarks and holds for climbing to the tree’s canopy. As the scar grows older, the ‘dry face’ becomes increasingly cracked and aged under the dramatically changing Australian climate3. Our sunburnt country’s intense weather makes the adaptability of flora and fauna an integral trait to survival in our scorching heat waves and wild storms. As well as this weathering, tool marks can also be found, etched into the bark decades after the scarification process4.

Found mostly across the east coast of Australia, some scarification happens naturally, through animal interference or wild weather, which can sometimes be mistaken for evidence of deliberate cultural scarring. Authenticating scar trees can be highly challenging and it is difficult to find elders who can confidently identify their original purposes.

The look of those scars was so familiar that I had thought they formed like this naturally. Whenever I find myself drawing a tree, this is exactly what they look like. I must have seen them so many times in the past at home in the country, and not even realised their significance, or the cause of their shapes. Years of kindergarten-drawn forests all feature a darkened oval in the centre. Years of bush walks back home contain the spattering of these peaceful gums lining the river.

I think back to scribbly tree drawings, perched at a primary school table sprawling my latest brown and green masterpiece; those trees were almost identical to the second, more aged scar tree I saw at the MCG. To me, this is how a tree looks: a canopy of leaves, green branches, a thick trunk and that iconic scarring right in the middle.

Hearing the term scar tree and seeing the gum at the MCG—I was struck with an image of my home’s bushland. These trees looked just like the one I had seen over 300 kilometres away in the country. Learning as much as I did on the cultural walk, I was excited to go back and visit the place that is still very much home—hoping to walk the track with more informed and perceptive eyes.

When I returned home during university break, I went on my usual morning bush walk. It was on the border of New South Wales and Victoria, where the great Murray River splits the land down the middle. It was the first day of spring and the wattle trees were in bright, brilliant bloom—the bush lit up in a yellowish hue.

I crossed over the Bullanginya bridge to the Barooga State Forest, I inhaled a deep, calming breath of soothing bush air; and enjoyed the peaceful comfort of home before the uni break ended.

I had walked this track,smoothed and defined from decades of people's feet, horses’ hooves and tire marks, my whole life—but that day was different.

I approached a tree, an eminent gum—rotund and sturdy, with various irregularities and grooves present in the centre of the trunk. I thought this might be the scar.