PERCEIVING THE PRESENT

A sensory mapping of land

A coastal lookout onto Port Phillip Bay, Point Wilson

Silently eroding on the fringes of metropolitan consciousness, Point Wilson is a vast and seemingly impenetrable landscape. Located on the flat expanse between Melbourne and Geelong, the land is a sun-beaten thing, its coast jagged and carbon black. To envision life here, one must look beyond the coast’s intimidating scale, draw upon a sense of the unknown, the invisible, yet few do. After all, imaginary sightseeing has never been a national pastime.

Perhaps tourists were deterred by the visceral textures; the viscous slop of mud underfoot, the salt frothing against sloped concrete, the languid shoreline sharp with broken shells. Against the carbon rock, serrated and acerbic with salt, even the tide departs with a sigh.

But the land was not always so hardened.

Life was once rich here; marshes full with salt, the air pregnant with the beating of wings. Ensconced by a generous coast, its horizon unmarred and unbounded, for centuries the waves rose and fell, lapping the land into fertility. A vital habitat for migratory bird species and shellfish, its vast plains would’ve once shouldered the weight of native wildlife, housed its bodies, fed its young. However time has seen the land depleted, the slowing of its ecological pulse, the alienation of its Indigenous people, its distancing from contemporary consciousness.

Exhausted through cycles of pollution and abandonment, the land no longer sustains us, nor we it. Invasive weeds envelop the plains and pools of muddied water gather on the once fertile soil. Cordoned-off from public access, its natural and cultural ecologies diminish, the once buried stories now rotting, unheard and unsung. Yet between armament and abandonment, colonisation and conservation, the land perseveres, dispersing in the wind suggestions of secret histories, of ambiguous futures.

Then again, piecing together these stories will not prove easy or linear. After all, it took a wrong turn to find my place here. It will take much more than that to unearth its past.

REMEMBERING THE PAST

Discovering the land within its archived histories

View from Point Wilson Rd. leading to Point Wilson

Bound between sun-beaten tarmac and flattened grassland, all roads leading to Point Wilson—be them layered or carved, they eventually give way to uninhibited space, a flat expanse of land, and a sea that stretches outwardly towards the horizon. Here, space is wealth. A vantage point. A gathering site for unsettled thoughts. Only this sense of richness is easily mistaken as void; and history has seen the land shrouded in both linguistic and governmental exploitation.

Trawling through defence department reports, my initial research yields a dense yet taciturn documentation of the land’s abuse through time. A report by the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works (1998) imposes the need for ‘tolerable risk’ and ‘cost-effective solutions’; linguistic justifications for the establishment of an explosive ordnance. Words, like scalpels, dissect the land in terms of economic profitability and the ‘extensive and expensive’ measures required to maintain its reduced functionality. The report speaks of scars: ‘corrosion’, ‘breakdown’, numerous ‘damaged shipping containers’ left by the establishment and subsequent reduction in defence facilities.

Condemningly, the document declares the land’s various inadequacies as an ammunition drop-off site. First, the shallowness of its bay, then later, the $200 million dollar budget required. It takes several subsections of the committee report to reach the more regrettable, longitudinally framed conclusion: the unacceptable depletion of native ecologies. In the spaces left between these documented activities, I’m told a plot of cyclic exploitation: the casual dumping of hazardous chemicals, the building of a 2,700 metre jetty in the late 1950s now unused, and the establishment of four naval armament storage facilities in 1981 scattered thirty-two years’ worth of explosive materials across the land.

Unsurprisingly then, despite this plethora of words, few give voice to the life bearing nature of the land itself. Warped in impersonal authoritative language, dense reports deaden the land, relegating it to the purgatory of cultural amnesia.

Now twelve years into its gradual reduction in armament activities, Point Wilson is incarcerated, held stricken under an ambiguous quarantine. The land is vacant, depleted, seemingly devoid of animal and human presence. If language is the weaving of memory, of life, the earth too, rarely sings.

In this silence, I wonder of the secrets buried within the earth.

Do they rot the land? Do they nourish it?

Warped sign along the coast at Point Wilson

Attempting an expository, recently erected signs mar the plains, haphazardly placed, weaving a fragmented tale of ecological conservation in the face of the increasingly diminished ability to sustain endangered migratory birds. Fittingly, some signs are wind-bent, angled at half-mast, sorrowful in their partial expository; others are staunch, cautioning visitors from prolonged dwelling, noting the increasing diseases among native bird species.

Caught in this purgatory between cumulative pollution and contemporary conservation efforts, the overwhelming sense of cultural absence permeating Point Wilson could seem a blessing, a respite from the encroachment of humans. But under the stark glare of a backlit sky, the silencing of voices—land borne, animal and human—is a swan’s song. It is a frail and tenuous lacking, a silent alarm, this collective amnesia of shared stories.

LISTENING TO INDIGENOUS VOICES

Recalling life on the land through Traditional custodians

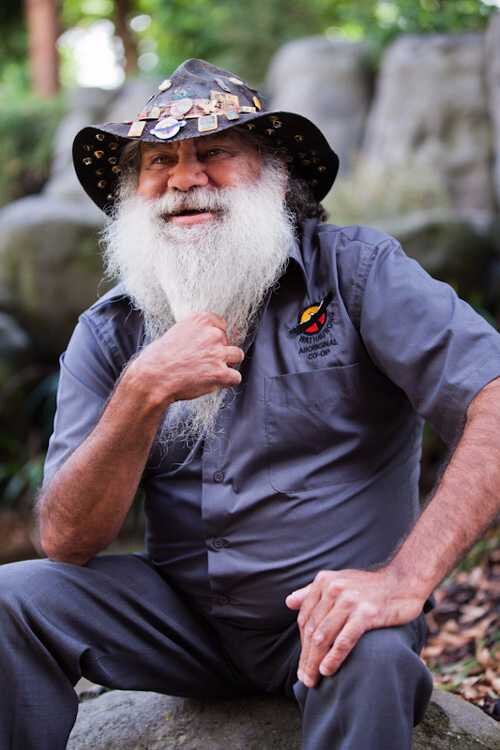

David Tournier, photo courtesy of the Wathaurong Aboriginal Co-Operative

Somewhere in the space between Point Wilson’s armament histories and unsuccessful conservation efforts, my mind stretches into the realm of the unwritten; the omitted and oppressed voices of the Indigenous community, the Wathaurong (Wadda-Warrung) people. I wonder of the songlines, how the country was first nurtured by language, preserved on the tongue over 25,000 years, rhythms unfurling, the shore—a revelation measured and remeasured across time through the embodied, the aural.

I cannot wander far into imagined soundscapes before the sudden intrusion of colonialism, a trade language which bound the land in terms of ‘terra nullius’, ambiguity to be claimed, owned. These words, woven into collective syntax and so removed from textures of the land, enforced the systemic oppression of Indigenous people and justified the exploitation of natural resources. When I find myself speaking to Wathaurong Elder David Tournier, he too, notes the power of language in denigrating or preserving the land.

“Over the years, different groups have tried to stop people from understanding what’s happening, whereas if you look at Aboriginal languages, they’re land based languages. So those other languages deal with economics—our language deals with the environment of the land out there. It’s not hard to learn. Language, depending on how you use it is a very powerful thing, and some people tend to use that language as a power.”

It takes a cursory glance at Australia’s colonialist past and archived documents to realise language’s capacity for ugly things. Perhaps recent discourse shrouding the land now, similarly renders the earth barren in our cultural memory. Hearing the stories of the land, its past usages, its resonance among the Wathaurong community, I am reminded again of how our words have also the capacity to breathe, to instil authority onto places, to incarcerate; marking them void, or singing them to life.

Map of Aboriginal language areas in Victoria, photo courtesy of the Wathaurong Aboriginal Co-Operative

Indigenous songlines are one such example; shared across time, between generations, and different language groups through a communal melodic expression. The song passes through the land the way it is intended to be remembered and traversed; the observation of landscapes follows the song, and it is understood that this continuous singing nurtures and preserves native ecologies.

So unlike the trade languages and dispassionate government reports, there is a richness and urgency to songlines which demands our collective listening. In a land bound by jargon, the preservation of natural and cultural ecology is a matter of negotiated words.

In this, I wonder of my own aural contributions to the land, how they sound alongside Wathaurong songlines, echoing through time. Do my words reclaim narratives, or contribute to archived ones?

And what of the land’s own rhythms—its ebbs and flows. Do our collected voices collide or harmonise? And what songs are lost in the absence of our listening?

INSCRIBING THE FUTURE

Observational poetics on life and land

Along the coast line, Point Wilson

At my feet, waves lap at disused boat ramps, eroding the sloped concrete. The wind passes through the bay, carrying with it to the city residues of salt and sand. Overhead, gulls hover, suspended in the stratum between sea and sky. Only the click of my camera shutter disturbs these seaborne rhythms; there is a melody to this, sung into the memory of those who choose to listen

But this song is a tenuous one.

Year by year, strains of avian botulism and continual habitat erosion have dwindled down the number of bird species, and on an off-season day, you can hear their growing absence. Like a siren’s song or a question unanswered, I find myself both mesmerised and alienated by the unnatural quietness, the land’s stilted pause.

My attention turns to the only other visible presence, two men perching upon the shoreline a few paces from me. Carrying binoculars, the men watch the gulls, fixated. When I gaze alongside them, they turn to me, surveying my pause, tell me that they’re birdwatchers. I stay with them a short while in their taciturnity, learning of their findings, their comings and goings on the land. In our silence, few sounds break upon the shore: gulls calls, the rush of the tide, and the distant blare of traffic. A fragmented song, these aural remnants of metropolitan life sit uncomfortably within the land’s contours, reminding me of my own unfamiliarity with natural spaces.

‘It’s an internationally renowned place for bird watching, any birdwatcher worth his salt knows that’ they say, and I find myself straining again to hear the land’s song. Perhaps, if I pay enough attention, hear the calls of rare birds and other animals, I too might find myself transfixed.

This song is quieter than that of the men’s speech, and my own humming. If we are to remember the land to life and let it harmonise our rhythms, its natural and cultural ecologies must both be given a voice and we in turn, must listen to them.

Somewhere beyond the grass in the slush of the sand, an unfamiliar song resounds. Pulled by a gravelly resonance, I follow the sounds, my feet slipping on muddy weeds. Crouched in the sand, three women scrape at the shore with plastic buckets. They are rhythmic, their eyes focused, wiry hands moving fast as they mark the earth, collecting sand worms for bait. Practised in their movements, there is a strong conviction to their barefooted rummaging and though I cannot understand their conversation I feel at once a sense of ease and familiarity, as if this moment has occurred before.

Listening carefully, I trace their linguistic cadences in an attempt to understand their shared heritage and contextualise their present activity. Their language is familiar somehow. Is it Vietnamese? Khmer? Or Burmese perhaps?

“I am unsure of specificities, but I notice how the language mirrors the form of the jagged shoreline, sharp with consonants, rounded with a full-bellied laugh. ”

Perhaps they are bantering, sharing anecdotes, or trading jibes. Perhaps they are refugees or tourists or established residents of local areas. At moments, their voices merge into a steady humming as they sing alongside one another in their decisive gathering on the land. Perhaps the details are inconsequential.

Singing and scraping, transfixing in their synchronicity, they are undeterred by my body’s awkward pause. I do not ask where they are from nor demand of them small talk. Gazing outwardly at the sea and the sand alongside one another, we are separate yet together in our presence here. Perhaps this is a song in itself, a composition made of bodies.

Moulding the landscape with their voices and hands, I wonder if they too, like me, were once unsure, confronted by its rugged plains. Singing outwardly, perhaps their voices might stir the land, slow its erosion somehow and dispersed in the wind, stir us to it again.