Me in Mum’s photos of me

Ben Muster

Mum.

Sometimes I look at photos you’ve taken of me and it’s hard to see myself in them.

That’s not me having a go at you, because you’ve got skills. You’ve been a pro at photography since before I was born. An actual pro.

I’ve realised that I should be grateful that I never had to pay for photos of myself. But, yeah, with the way you take them, I can’t always say for sure ‘that’s me’. It might be to do with how I’m posed and what I’m wearing, because I know that’s not how I would’ve set myself up naturally.

Sorry, I don’t want to come off like I’m complaining. I’m not. I don’t want to dredge up anything we’ve gotten past already.

I’ve been pretty vague telling you what I’ve been doing at uni, but I’ve been studying an artwork by this guy called Ali Tahayori. It made me think of you.

The Archive of Longing he had up at ACCA recently was his 2024–25 series, and the basis of it is a collection of photos he inherited from his mum. Of her and of familial things. He retook the photos, printed them on glass and put all kinds of cracks in them.

He said he saw them differently compared to how he did when he was younger. And, even with ‘the photographer’s agenda and the subject’s intentions’, he’s reassembled his own interpretation of them.

Part of what he wants to show are details that he sees to be there but aren’t necessarily captured on purpose. He’s pointing out that there’s always something going on, and often there’s allusions to those things that turn up in photos. Regardless of whether the person wanted there to be. At least, he wants to express what these photos bring up for him when he looks at them now.

He mentions how being queer affects that—that he can pick up on certain ideas in these stagnant images because of it. I do mostly get what he means, but I can’t explain it. It’s like when you’d start watching a show with me part way through, and I’d struggle rushing to tell you what was going on. You weren’t there from the beginning, so it’s not really the same experience.

The cracks that Tahayori makes in the photos are called Aine-kari, but that’s spelt differently sometimes. It’s an Iranian technique of covering something with pieces of reflective glass, usually just for decoration. But Tahayori says he does it to ‘reflect on topics such as identity, queerness, and otherness while questioning the nature of representation’.

There are parts of the photos you’ve taken of me that reflect what I think are my memories. I see them bordered in hard, red lines.

I’m not trying to fuck your photo up. Sorry to say ‘fuck’.

This photo is an exception to how you’d always get me to smile in the way that I didn’t like. It’d crease my face up and I thought it made me look gross. I still think I look not ideal, but this is a face I can identify as one I pulled all on my own.

I look at this photo and I remember that you took it at the river for when I was doing deb, and that I felt like shit basically the entire day. Sorry to say ‘shit’, but that’s the truth.

I remember the hired suit being stiff and so uncomfortable, and that me and Daniel had to not get them dirty. And I remember I told Daniel that him and his partner could get their photos done for free by you, without asking you first. I did that because I wanted to hang out with Daniel more, even if it involved seeing him with a girl. They’re out of frame, but I’m very aware that they’re there.

I’m not sure how accurate it is to say that I have an interpretation of your photo—I know factually how I was getting on, but that’s not how the photo’s representing me.

It’s just of a guy in a suit leaning on a tree and doing a fucked face. I’m probably going to say ‘fuck’ a lot.

I tried articulating how much those feelings for Daniel scrambled me, but there were nuances I couldn’t communicate. Same as how there’s heaps that’s happened to you that I’m not going to fully get.

How much I liked Daniel and how I was disgusted with myself for it—that’s not what you set out to capture, but it’s what I see when I look at that photo.

In his book on art criticism, Ways of Seeing (1972), John Berger says that ‘Every single image embodies a way of seeing. Even a photograph […] Every time we look at a photograph, we are aware, however slightly, of the photographer selecting that sight from an infinity of other possible sights’.

I have to say where I’m getting this sort of evidence from so you know I’m not making it up. I’m not having an argument with you or anything, I’m just explaining.

You had the chance to show me constantly wanting to talk to Daniel, or to show him doing the fair thing and talking to his partner instead, but you snapped me like I am in that photo.

I remember asking you to take this one, which I didn’t make a habit of. It was when I needed a headshot for a casting call.

My hair was growing back after I’d had the impulse to shave it all off. You made me wear an inoffensive white shirt and told me how to pose against one of our walls.

I don’t like standing at that angle. It makes a chunk of the left of my face (your left) look shrunken through my glasses. To be fair, it was surely as presentable as you could’ve made me. It was when I was stuck at home for the lockdowns and had no fucking idea what I was going to do with myself. And it’s all a bit blurred for me, but I think that was when I started on antidepressants.

It’s a good photo, though. It just unnerves me to remind myself that it’s me in there and that’s what I used to be like.

But I know someone else looking at it wouldn’t see all that the same way.

I’m almost certain I submitted that photo to be considered for the reboot of Heartbreak High (2022). This semester, some of my classmates were saying that the show doesn’t represent Australian experiences truthfully. To me, it does, and I think they’re just way more sensitive to media they see themselves represented in.

More critical of it. And I’m not exempt from that.

This guy Christoph Ribbat wrote about separate ideas of ‘straight’ and ‘queer’ photography. The ‘straight’ photos are ‘technically perfect, non-manipulated, honest, simple’. But a lot of the notable names in that practice seem like dickheads. In their terms, the originals of Tahayori’s photos in Archive of Longing were more ‘straight’, and him altering them was making them ‘queer’.

Neither approach is more realistic, in my opinion. I’d say they’re their own versions of the truth, their own perspectives. Reality filtered through an artist and represented differently.

I remember feeling fucked during the taking of that last photo. Not that you taking photos of me made me feel fucked, that’s just what was going on in that moment. You couldn’t help that you captured that, like I was explaining earlier. Yeah, I wasn’t doing great, but as far as that photo’s concerned, I was.

You can take a picture of anything and represent it as straight. Not straight like ‘straight’ photography, but as in heterosexual. There’s this Melbourne-based couple called The Huxleys who make queer art, especially photos. You should look them up, they’re cool. But in a lot of other outlets’ photos of them—if they’re getting interviewed or whatever—you can’t be certain which way they swing. Similar to that, I was astounded to learn that James Corden is straight. That’s on me, though. That was my perspective.

Whenever you’d take photos of me and get me to flick through them and choose which I liked, I’d pick the ones I thought I looked best in. Except, if there weren’t that many of those passable ones, does that mean the pictures I didn’t like were a better representation of me? Even if I wasn’t keen on how I was being represented, were they the ‘better’ ones?

I don’t know.

In her writings about motherhood, Julia Kristeva presumed to know how mother–son relationships work when there’s a gay man involved. She’s addressed by Michael du Plessis, who highlights her saying ‘male homosexuality [is] a double confinement: that of the mother in the gay man, and of the gay man in his mother’s image’ to iterate how generalised and unfair that is.

Still, I think that argument of Kristeva’s is sort of why I didn’t like getting my photo taken. I remember getting so restless with you instructing me how to position myself, and even if it was awkward as, to hold still. You were making me appear how you wanted me to, and when you took the picture, I was literally in your image.

I don’t want to word it harsh but that’s the only way I can. I’m just trying to put it all out there.

In taking photos of me, I’m assuming there was the goal to have me represented in a way that was in line with your style. Of course, that style wasn’t always going to be exactly the same as mine.

When I first saw Archive of Longing, I thought that all those cracks that Tahayori made in the photos had to do with him not liking them and wanting to smash them apart into shards. He might’ve done that to a couple of them, but surely not the whole series. I’d get pissy with you whenever you’d tell me you were planning another photoshoot, I remember. And we have talked it out, but I am sorry.

Anyway, that ‘confinement’ thing is such shit. It’s a framing of a concept that Kristeva doesn’t fully understand. You are my mum and you raised me, so of course we share traits. And that has made us clash, but to me it just proves how alike we are.

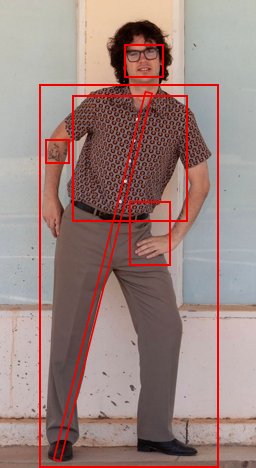

This photo is one of my faves. You still picked out an outfit for me and you were still occasionally telling me how to stand, but mostly you were saying ‘Pose!’ and letting me strike them.

I’ve tried to find profound differences between this shoot and the previous ones, but I can’t. My hair had grown back, but the face I was pulling wasn’t any more photogenic than it tended to be. Two of my tattoos are there, and I present as fairly gay, but I’d gotten over being insecure about the latter by then.

It was so good coming back home to get these taken, and visiting everyone. Parts of what I like in this photo have nothing to do with what’s technically visible, but they’re there for me when I look at it.

I used to be so concerned with how your photos represented me. I know now that it didn’t matter, because they’re such good photos. And it is me in them. It’s how you saw me, which is just as realistic as how I saw myself. Archive of Longing isn’t untrue; it’s just another way of seeing.

Trying to intellectualise and overanalyse these photos is only going to fuck them up. I am not just an image in my head. I can wear the clothes that I want and pose how I want, but, inevitably, everyone’s going to take the ways they see me and run with them. They’re going to see gay as straight and straight as gay, and maybe they’ll see these photos and think I get a lot from my mum.

As I go through my life—like wandering through a gallery—I see so many representations of me reflected back. Glinting off everyone in special ways.

Tahayori inherited his mum’s photos and created what he couldn’t have if she hadn’t organised the originals. Having all these photos of me is a reassurance that I’m remembered, and that I’m cared about, so I’m sorry for ever seeing them as anything else.

Because you could’ve taken photos of anything, and you took photos of me.

Ben Muster is currently completing his Bachelor of Arts (Creative Writing) at RMIT University. A writer who grew up in regional Victoria, his stories scrutinise the collisions of Australian masculinity and queerness. His recent work in creative non-fiction refers to photographs of himself where he reflects on the nature of representation.

All pieces thumbnail credits: Ali Tahayori, Archive of Longing 2024–25 series (detail), installation view, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Narrm/Melbourne. Photograph: Andrew Curtis

Image credits: Ali Tahayori, Archive of Longing 2024–25 series, installation view, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Narrm/Melbourne. Photograph: Andrew Curtis

Photo 1: Author as a teenager standing next to a tree. Red boxes outline key elements, © and image courtesy: author family archives, accessed 07/10/2025

Photo 2: Author headshot with red boxes outlining key elements, © and image courtesy: author family archives, accessed 07/10/2025

Photo 3: Author full body shot with red boxes outlining key elements, © and image courtesy: author family archives, accessed 07/10/2025